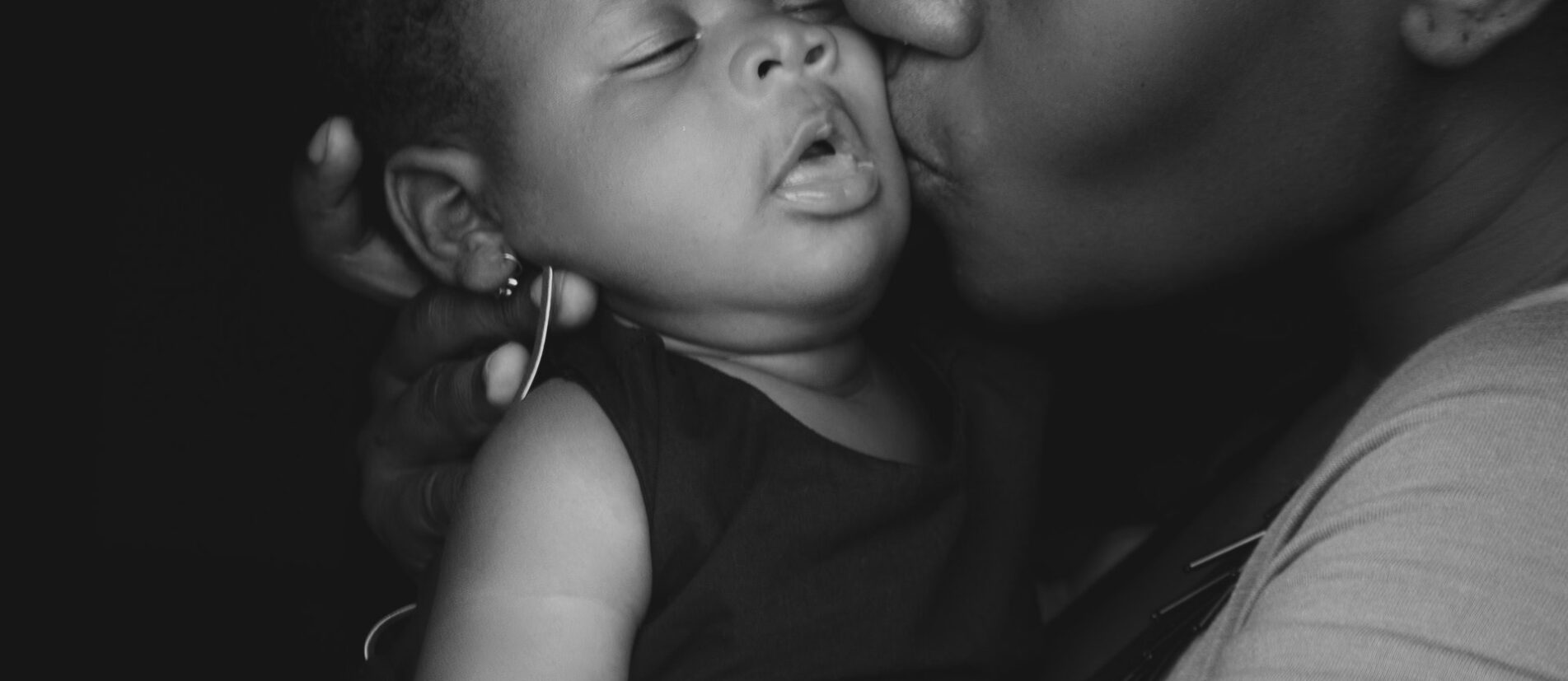

Moms of color have an increased risk of experiencing postpartum Depression more like depression in silence than women in other ethnic groups. Nevertheless, fear is keeping them from getting the treatment they need. Here’s why, and how black families can get the right mental health support.

Statistics show that Black women are three to four times more likely to die during or after delivery than white women. From 2011 to 2015, there were 42.8 deaths per 100,000 live births for Black non-Hispanic women—a higher ratio than any other ethnic group. “These statistics along with birth trauma and untreated mental health issues prior to and during pregnancy may lead to postpartum depression,” Odom says.

Postpartum depression, anxiety, and other perinatal mood and anxiety disorders can affect any mother and can manifest up to one year after delivery. However, there are cultural nuances that can increase the risks of experiencing PPD for Black mothers.

Karen Flores shares her experience

I was extremely anxious and ashamed thinking that I was losing my mind and that my baby would be taken from me. I tried praying and did a lot of cardio.

During her 1st year, Karen Flores was afraid she was not emotionally stable enough to take care of her daughter. On the particularly hard days, Flores would take a walk with her daughter on the beach.

“Out of nowhere, this bizarre thought came to my mind ‘push the stroller over the rocks and see what happens,’” she wrote on the site Maternal Mental Health Now.

“I was paralyzed by the thought but forced myself to keep on walking while wondering where it had come from—’Oh, My God, am I crazy?’ I wondered.”

Flores, now 50, was suffering from postpartum depression, a condition that affects up to 1 in 7 women, according to the American Psychological Association. But, Flores didn’t immediately seek out help.

Before her daughter’s second birthday, she began working with a therapist to manage the symptoms of her depression.

Besides, black women like Flores are less likely to get help for postpartum mental health issues compared to both white women and Latinas, according to a study published in the journal Psychiatric Services.

That’s is because this part of this hesitation is caused by fear. These women fear they will be considered unfit and have their children taken away from them by Child Protective Services.

“Many medical practitioners are not trained to refer or treat perinatal mood disorders so when they hear patients report typical symptoms of postpartum depression, practitioners mistake the severity of the symptoms for abuse.” Odom, who is Black herself, adds that many practitioners do not recognize a difference in how perinatal mood disorders present among ethnic groups.

Suffering in silence

Odom says she often sees the same themes preventing Black mothers from seeking mental health therapy. First, there’s the fear of losing control, independence, respect from others, or mental sanity.

“Sometimes holding in this fear leads to a manifestation of irrational thoughts—’I’m not a good mom,’ ‘I feel empty,’ ‘I’m not emotionally connecting to my baby,’” she says. “The belief that something is wrong, which must mean I’m doing something wrong. I’m a bad mom is an extension of these irrational thoughts.”

Then she often hears that these women would prefer to seek help from their closest ones. Like, friends, family, and church rather than a mental health professional.

“Some believe that if you go to therapy you have to be admitted to a psychiatric hospital or will be required to take addictive prescription medications. Some people’s religious beliefs also shape their views on mental health and can impact their help-seeking behaviors.”

Moreover, there’s also concern passed down from generation to generation that mental health practitioners are suspicious of Black mothers.

Help comes with a risk

In her professional career, Rattigan has observed well-intended agencies and clinicians overlook entire communities. This could benefit from mental healthcare-related prevention and early intervention services. She’s also seen disproportionate reporting of suspected maltreatment or neglect in these same communities.

Rattigan says she is heartbroken when a report she makes exposes a Black or brown family to a system. Since she is the mandated reporter in her community. This may not fairly evaluate the need to remove the children due to racial bias and discrimination. Not all reports Rattigan makes are for children in immediate danger.

Maternal health care

The Perinatal Mental Health Alliance for People of Color provides education, resources, and support for individuals, families, and communities of color around perinatal mental health and wellness.

In addition, Better Postpartum teaches mothers ways to avoid or alleviate these mental health disorders. Postpartum Support Virginia encourages pregnant mothers to take birthing classes that include information on depression and anxiety.

Postpartum Support International offers a free helpline that moms can call 24 hours a day. Through this service, moms leave a confidential message and trained volunteers return the call or text and answer questions. They offer encouragement and connect callers with local resources as needed.

When MTV teamed up with Every Mother Counts and the Black Mamas Matter Alliance in May 2019. It gave hope that future generations of Black women will have better maternal health care than what is available today.

This #SaveOurMoms campaign sheds light on the fact that every day two to three women in the U.S. die from pregnancy-related complications and Black women are at the greatest risk.

“If all women receive the same quality of care, then there would be no need to have specific care for Black women in the future,” says Kay Matthews, the founder of the Shades of Blue Project, an organization dedicated to helping minority women with PPD.

For help, call the Postpartum Support International helpline at 1-800-944-4773 or send a text to 503-894-9453.